(Spanish here)

For Silvia, the neighborhood has been her playground, her place of welcome, the place where she grew up and where she says she will give birth, together with her partner, to her first child in a few weeks.

A few minutes from Toledo, on the border between the departments of Montevideo and Canelones, there is a Uruguayan community of about one hundred families, with more than 8 children in some of them.

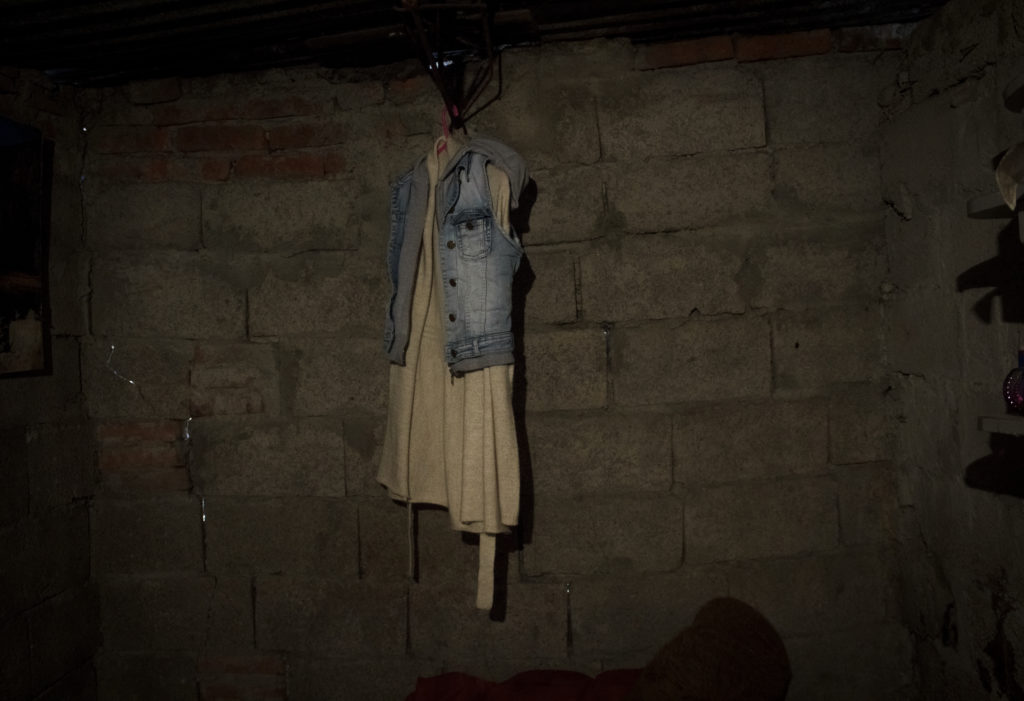

The settlement has progressed in quality of life thanks to the community, who has managed to organize itself to improve the material of the houses, initially ranches improvised of people displaced by the 2002 financial crisis that affected the region.

The non-profit organization TECHO aims to fight against inequality, seeking to overcome the situation of poverty that thousands of people live in the irregular settlements, through the joint action of the neighbors who live there and young volunteers articulated with other actors in society, encouraging action and social awareness. The implementation of a community work model in Los Hornos settlement has been key for the construction of, among other things, emergency cabins for families that had no roof.

However, the legal situation remains irregular, so they can not get basic services such as sanitation; causing pollution of soil and the danger of infectious diseases caused by the septic tanks that each dwelling must maintain.

The neighbors know each other well. Beyond the existence of some drug mouths and the occasional shootings that are heard some nights, the community says it feels calm and develops its life normally during the day.

This is a series about some of the stories that happen in the day to day of the neighborhood. Their faces and only a handful of their details.

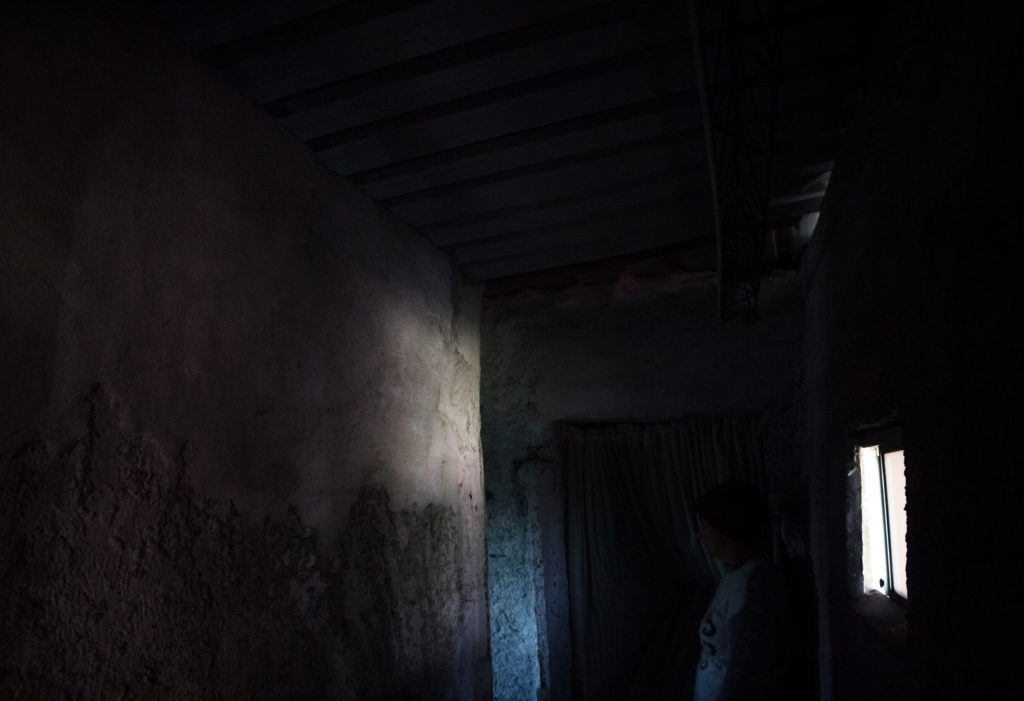

Miguel de Ibañez shows his house with a tired face. In it, he lives with his analphabet mother and he complains of the humidity caused by the lack of gutters around, as well as the leaks that fall through the holes in the sheet that serves as a roof. The wet smell and the cold walls are felt when entering the room which in turn serves as kitchen and bedroom.

Vanessa’s children are distracted with their phones in the room, which is one of the better-groomed houses of the neighborhood, but nevertheless complain that their neighbors do not fix the overflow of their septic tank, which floods the patio of the house.

And meanwhile, after eating those tortas fritas -a typical Uruguayan food made of fried flour dough- that are sold at the neighborhood fair organized on weekends, Maria attends her husband, Efraín*, who must be kept with oxygen 24 hours a day. María is happy that she has been given an orthopedic bed for her husband, who has not been able to leave the sofa in a couple of months.

These stories and many more happen in these streets where football is played, laughs and neighbors are greeted every day, an hour from the growing Montevideo downtown.

*Efraín died due to his disease in December, 2018